-

Pigeons in the Arctic: Part III: Sir John Ross’s 1850-51 Search for the Lost Franklin Bay Expedition

We’ve previously written about how Arctic explorers relied on homing pigeons in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Recently, we uncovered facts demonstrating that Royal Navy personnel brought homing pigeons with them as they searched for the Lost Franklin Bay Expedition in the 1850s. Given that homing pigeons were very much a novelty amongst the British public at the time, this represents an early usage of pigeons in a British military setting. In this blog post, we examine Captain Sir John Ross’s 1850-51 search for the Lost Franklin Bay Expedition and how pigeons were used on this venture.

On May 19, 1845, Royal Navy officer Captain Sir John Franklin sailed out of the river village Greenhithe toward the Canadian Arctic. Commanding the warships HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, his task was to explore the uncharted sections of the Northwest Passage, a sea lane in the Arctic Ocean linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Although Franklin didn’t know it at the time, it would be the last time he and his crew members saw England. Following a July 1845 sighting by a whaling ship, the Franklin Expedition vanished into the mists of time.

By the fall of 1846, Captain Sir John Ross, a Scottish Royal Navy officer, sensed that something bad had happened to his old friend. A seasoned polar explorer, Ross possessed considerable experience in Canada’s Arctic Archipelago, an area that encompasses the modern-day provinces of Nunavut and the Northwest Territories. In 1818, he sailed through this region on the first Admiralty-sponsored search for the Northwest Passage. Ross ultimately failed to uncover any useful information during that trip, but he redeemed himself on a return voyage in 1829, where he recorded valuable geographical and ethnological information, for which he received a knighthood from King William IV.

Drawing on his deep knowledge of the Arctic, Ross knew that Franklin should’ve returned at this point. He felt honor bound to do something—indeed, Ross had promised Franklin that he’d personally lead a relief party if Franklin failed to return within two years. With 1847 just a few months away, Ross contacted the Admiralty with an offer to lead a search-and-rescue mission the following summer. The Admiralty denied his request, and renewed its denial when Ross raised the issue again in 1847. But in April 1850, the Admiralty bowed to mounting public pressure and accepted Ross’s offer.

At 73 years of age, Ross now found himself preparing for the third Arctic voyage of his career. To assist the relief expedition, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC)—the company that essentially ran much of Canada at this time—offered a generous sum of £500. With this donation, Ross wasted no time in organizing the venture. With little time to spare, he quickly obtained two ships for the voyage: the Felix, a newly built schooner, and his personal yacht, the Mary, which would serve as a tender. He then assembled a crew and outlined the parameters of the journey. As planned, Ross would sail to the Lancaster Sound in Nunavut, where he’d join four other relief missions and coordinate search efforts for Franklin and his crew.

Before leaving the United Kingdom, Ross sought a way to maintain communications with the outside world. Letters could be sent to the Admiralty and HBC officials, but mail delivery was slow and not guaranteed. Outside of traditional mail service, an explorer was limited to sending written messages either via balloon or in bottles tossed into ocean currents. As a last-ditch effort, a message could be deposited in a cairn on some island for future explorers to find. If any of these methods failed, it could be months or even years before the British public learned of Ross’s (and ultimately Franklin’s) whereabouts.

Ross rose to the occasion and hatched a novel plan: he would attempt to deliver messages through carrier pigeons while searching for Franklin. To that end, he procured four homing pigeons—both an older and a younger pair—from a Ms. Dunlop, a fellow Scot living at Annan Hill, near Ayr. Ms. Dunlop’s pigeons had considerable experience in message delivery; she had trained them “to keep up a correspondence to two friends at a distance.” Ms. Dunlop evidently was an early practitioner of pigeon racing, as the sport was largely unknown amongst the British public at this time. Commercial firms, press agencies, and government institutions in the UK had relied on pigeons for message delivery since the late-18th century. With the invention of the electrical telegraph, however, these institutions quickly sold off their pigeon stocks to individual fanciers, leading to the growth of a nascent pigeon racing culture, especially amongst the professional classes. In its infancy in the 1850s, pigeon racing would soon flourish with the first homing pigeon clubs popping up by the 1870s.

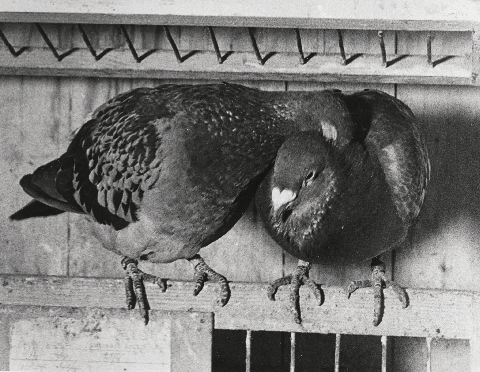

On May 23rd, 1850, Ross and his vessels departed from Loch Ryan. With his pigeons in tow, Ross devised a plan for their use on his expedition: two pigeons would be freed when he made his winter quarters and two more would be released if and when he found Franklin. The relief mission reached the Lancaster Sound in August, where they connected with the other relief ships. For weeks, a total of ten ships scoured the barren landscape for signs of Franklin’s expedition. Ross apparently told his fellow rescuers about his plans to send messages via pigeon—they reacted with considerable amusement. “[M]any people laughed at the idea of a bird doing any service in such a cause,” Lieutenant Sherard Osborn, an officer aboard the relief ship HMS Pioneer, remarked in a post-expedition account. “I plead guilty, myself, to having joined in the laugh at the poor creatures, when, with feathers in a half-moulted state, I heard it proposed to despatch them.” Ross’s correspondence, however, reveals that he held the pigeons in high regard. “[W]hat I place the most faith in [are] four well-trained carrier pigeons,” he wrote in an August 13th letter sent to an HBC official. “I hope they will be the bearers of good news.” One can’t help but wonder why Ross believed in the pigeons so strongly; did he have personal experience with Britain’s burgeoning racing pigeon community?

By mid-September, the region’s waters had started freezing over, as the Arctic winter set in. Ross’s vessels and the other rescue ships settled in at Assistance Bay, located on the southern shore of Cornwallis Island. The Bay provided natural protection against the fierce northern winds, so the rescuers thought it appropriate to make their winter quarters at the site. In early October, Ross decided to release his pigeons. Per his contemporary diary, eleven messages from various officers were scribbled onto tiny pieces of paper and fastened to the pigeons. Modern pigeon fanciers may think it absurd that Ross expected the birds to fly all the way back to Scotland, but Ross, to his credit, seems to have known better. Indeed, per contemporary accounts, Ross intended for the pigeons to alight upon “some of the whaling vessels about the mouth of Hudson’s Straits” and “they would take a passage to England.”

Yet, initial attempts to release Ms. Dunlop’s pigeons failed miserably; the birds merely fluttered about the “boundless expanse of unbroken snow and ice” for a while, then returned to the Felix. Subsequent releases yielded the same exact outcome. Crew members tried firing guns at the birds to frighten them away, but the pigeons still refused to fly away from the ship. Having been confined for months aboard the ship, it appears the pigeons now viewed the Felix as their home loft.

Not willing to admit defeat, Ross and his crew rigged up a contraption that would’ve delighted Rube Goldberg. As they envisioned it, an 8 x 6 hydrogen balloon with an attached basket would carry the pigeons off the ship and over the Arctic landscape. After floating for 24 hours, a cord of slow match–a slow-burning cord used in black-powder weapons–connecting the basket to the balloon would burn up completely, causing the basket to spring open like a trapdoor, liberating the pigeons into the wild blue yonder. To keep the birds well fed, “a little split peas” would be placed in the basket for the birds to feast upon “before leaving their temporary abode on their aerial passage.”

Eyewitness accounts are muddled as to the specifics of the balloon launch. Dr. Peter Sutherland, a surgeon attached to the relief ships HMS Lady Franklin and HMS Sophia, reported that Ross “sent off two balloons, with a carrier pigeon attached to each in a small basket.” Lt. Osborn’s memoir, in contrast, only mentions “two birds duly freighted with intelligence and notes from the married men” secured to a single balloon. Meanwhile, an account appearing in the Ayr Observer exactly one year later claimed that Ross attached the younger pair of pigeons to a balloon, then did the same for the older pigeons. The newspaper’s account mirrors the Felix’s logbook, which records two separate pigeon releases occurring on the evenings of October 3rd and 4th, respectively.

What happened after the balloons floated away remains unclear as well. Per Ross’s personal diary, the pigeons “went rapidly out of sight S.S.E. true.” Yet the author of the Lady Franklin’s logbook recorded an entirely different result: “At 4”20 minits [sic] it fell in the water and drowned the pigeons [sic] about 3 miles distance from the ships.” This discrepancy perhaps can be reconciled by considering a post-expedition account appearing in the Ayr Observer. According to this version of events, the younger pigeons’ balloon “rose beautifully, and [was] seen careening along southward, till lost first to the eye and then to the telescope.” In contrast, “the older pair . . . were unfortunately drowned . . . when about two miles away” the balloon faltered and “trailed along the ice,” dipping periodically into “the snow and water.” Crew members chased after the balloon and tried to salvage the precious cargo, but “the birds could not be saved.”

Adding to the mystery, on October 22nd, the Glasgow Daily Mail claimed that Ross’s pigeons had been spotted on October 18th, attempting to visit Ms. Dunlop’s dovecote. This account alleged that two birds had “arrived within a short time of each other” and that neither of them had carried a despatch. The account alleged that one of the pigeons “was found to be considerably mutilated,” evidence apparently of an attached message having “been shot away.”

Within a week, the press had added various details to the initial story. Per this rapidly evolving narrative, a homing pigeon had been seen perched atop of Ms. Dunlop’s dovecote on October 13th. However, because the loft was undergoing repairs and had been sealed off, the pigeon (and possibly its mate) had flown away. On the 16th, Ms. Dunlop received information that “a strange carrier-pigeon had taken refuge at Shewalton, the seat of the Lord Justice General.” The pigeon was brought to Ms. Dunlop, “who at once recognised it as one of the young pair.” Upon being taken to its old loft, the pigeon purportedly “flew at once into the nest where it had been hatched,” even though there were upwards of forty similar compartments in the building. The newspapers claimed that the “feathers under the wing were very much ruffled, where it is customary to attach despatches,” but observed that “the note, if any were attached, has been lost.” If these accounts were to be trusted, then one or two of Ross’s pigeons had flown over 2000 miles from Cornwallis Island to Ayr.

Not everybody was convinced by these reports. On October 30th, a Stretford fancier named John Galloway expressed his skepticism in a letter to the Manchester Guardian. A stockbroker by profession, Galloway had been a pioneer of pigeon racing in the UK; as early as 1840, he had been training his loft to fly from London to Manchester in four hours. His birds, per an account written fifty years later, “were reckoned to be the best in England at that time and that they were bred from Antwerp birds imported by the stockbroker.” With his considerable expertise in the affairs of pigeon racing, Galloway could not stomach the inaccurate reporting surfacing in papers throughout the UK.

Writing off the newspaper accounts as “the clumsy invention of some wag,” Galloway proceeded to poke holes in the emerging tale. He observed that pigeons would not fly away from their home loft as Ross’s birds had allegedly done—”they would remain at their old habitation until nearly famished with hunger.” He then argued that the damaged feathers under the bird’s wing were irrelevant, as fanciers typically secured messages to the pigeon’s leg and “would just as soon think of tying a letter to a bird’s tail as under its wing.” Finally, Galloway attacked the distance traveled. “[N]o such distance as 2000 miles has been accomplished by any trained carrier pigeons,” he declared. He pointed to a 600-mile race between Spain and Belgium in 1844, where “[t]wo hundred trained pigeons, of the best breed in the world” were released “and only 70 returned.”

A particularly stinging critique appeared from none other than Ross’ colleague and fellow Royal Navy officer, Captain Charles Codrington Forsyth. Franklin’s wife, Lady Jane, had recruited Forsyth to lead a private expedition to the Arctic Archipelago. But after spending a mere 10 days in August hunting for Franklin, Forsyth had ordered his crew to head back to Scotland, reaching the UK by early October. Forsyth had personally seen Ross’s pigeons aboard the Felix. The Captain was not impressed by what he’d observed. While the press was still in a frenzy over the purported return of Ross’s bird(s), Forsyth expressed his doubts to the British literary magazine the Athenaeum. “[T]he birds are very young and not likely to stand the cold of the northern latitudes,” he reportedly told the periodical.

In spite of Galloway and others throwing cold water on the enterprise, much of the British public nonetheless remained convinced that future messages about Franklin would soon be arriving on the wings of a pigeon. On Nov. 2nd, residents of the Scottish city of Dundee allegedly spotted a pigeon “hovering about with a letter attached under one of the wings” near some ships along the River Tay. “Of course, there was no other conjecture but that it must have come from the Arctic regions with intelligence of Sir John Franklin, ” the Dundee Advertiser reported, “and the eagerness to get possession of the winged stranger was very great indeed.” The bird alighted onto a ship’s rigging, but flew away when people approached it. Later, it was reported to great dismay that the pigeon had simply traveled from nearby St Andrews.

Writing from the vantage point of 174 years later, it is difficult to make judgments. Nevertheless, a pigeon flying 2000 miles over snowy terrain and oceans in just under two weeks strains credulity. While modern-day, elite racing homers can fly 500 to 600 miles a day, in the mid-19th century, the breed was still in its infancy, especially in Britain. In 1842, for instance, pigeons liberated at Liverpool took nearly 12 hours to fly 300 miles to Brussels, Belgium. A similar race was held between Hull and Antwerp, Belgium in 1846. The fastest fliers made the trip of 280 to 300 miles in seven hours, while the remainder took upwards of a day. Notably, none of these racing pigeons were British natives, as evidenced by their homing to lofts in Belgium. At best, we can say that Ross released a pair of pigeons via balloon over the Arctic Archipelago in October 1850; everything afterwards must remain a matter of speculation.

Ross ultimately returned to the UK in late-September 1851 without any insight into Franklin’s fate. Despite media reports, his efforts to communicate by pigeons likely failed. Instead of tying his pigeons to balloons and hoping they’d land on a passing whaling ship, Ross would’ve been better served depositing the birds at an accessible HBC trading post and instructing the facility’s personnel in the finer points of flight training. If Ross had done this, the pigeons may have regarded the outpost as their home loft, setting them up to be distributed to the relief vessels. The ships, in turn, would’ve been able to remain in contact with the outpost as they searched for Franklin. Ross’s failure to attempt such a feat reveals the overall ignorance of homing pigeons’ flight abilities during this period. Still, the possibility that pigeons had returned from the Canadian Arctic excited a British public desperate for information about Franklin, especially Lady Franklin. In our next blog post, we’ll take a look at two more relief expeditions occurring in 1851 and 1852; inspired by Ross’s example, the individuals in charge of these missions brought pigeons with them for use in the Arctic.

Sources:

- “A Pigeon Race,” Manchester Weekly Times & Examiner, Jul. 25, 1846 at 3.

- “Arctic Searching Expedition,” The North British Review, Vol. X, No. 1, May 1851, at 255.

- “Carrier Pigeon,” The Glasgow Daily Mail, Nov. 6, 1850, at 4.

- “Carrier Pigeons,” The Zoologist, at 3709-10, Vol. 10, 1852 (citing Lieut. Sherard Osborn’s “Stray Leaves from an Arctic Journal, at 174).

- “Despatch No. 2,” The Times, Oct. 1, 1850, at 8.

- Galloway, John, “The Reported Return of Sir John Ross’s Carrier Pigeon to Ayr,” The Guardian, Oct. 30, 1850 at 8.

- Johnes, Martin, “Pigeon Racing and Working-Class Culture in Britain, c. 1870-1950,” Cultural and Social History 4(3):361-383, September 2007.

- “Latest from Sir John Ross,” The Glasgow Daily Mail, Oct. 22, 1850, at 2.

- Old Hand, “The Racing Pigeons and Pigeon Racing for All – Vol. I” (1966).

- “Our Weekly Gossip,” The Athenaeum, No. 1201, Nov. 2, 1850.

- “Pigeon Race,” Sheffield and Rotherham Independent, Aug. 6, 1842, at 7.

- Ross, W. Gillies, Hunters on the Track: William Penny and the Search for Franklin (2019).

- “Sir John Ross and the Carrier Pigeons,” The Glasgow Herald, Oct. 3, 1851, at 6.

- “Sir John Ross’s Carrier-Pigeons,” The Leicestershire Mercury and General Advertiser for the Midland Counties, Oct. 25, 1851, at 4.

- “Sir John Ross’s Carrier Pigeons,” The Standard, Oct. 29, 1850, at 1.

- Sutherland, Peter, Journal of a Voyage in Baffin’s Bay and Barrow Straits, in the Years 1850-1851, Vol. 1, at 403 (1852).

- “The Carrier Pigeons of Sir John Ross,” The Observer, Oct. 28, 1850, at 7.

-

“Little Feathered Heroes”: Camp Pike’s Pigeon Service, 1917-1919

-

Pigeons in the Yugoslav Wars: The Croatian War of Independence (1991 A.D.)

In reading about military pigeons, one might be tempted to think that such services ended after the Second World War. For the most part, that’s accurate. Once electronic communication became cheaper and widespread in the post-war era, most militaries happily disbanded their pigeon services, eager to get rid of a seemingly archaic system. By the 1990s, only Switzerland’s Army boasted a fully fledged pigeon service and even that was phased out after voters slashed the military’s budget in 1994. Yet, unbelievably, pigeons were used to relay wartime messages as recently as 1991. This week, we take a look at how Serbian fighters in the Croatian War of Independence relied on pigeons to carry messages back home to loved ones.

In 1991, a series of geopolitical upheavals erupted across the globe. On January 17th, an international coalition led by the United States wrested Kuwait from Saddam Hussein’s control. Exactly five months later, lawmakers in South Africa repealed apartheid legislation, paving the way for a multi-racial government. And on Boxing Day, the Soviet Union officially dissolved after more than 70 years of rule.

Amidst this tumult, Yugoslavia—the great hope of South Slav nationalists in the aftermath of World War One—plunged into chaos. Composed of six constituent republics and two autonomous provinces divided roughly along ethnic lines, the nation saw a sharp rise in secessionist movements following the 1980 death of longtime President, Josip Broz Tito. On June 25th, 1991, the republics of Slovenia and Croatia declared independence. This inflamed tensions with the republic of Serbia, the largest and most dominant region in the country. Serbian officials sought to preserve the Yugoslav federal government, regarding the independence attempts as illegal and unconstitutional. Ostensibly to protect Serbs living in Croatia, the Serb-dominated Yugoslav People’s Army invaded the region on September 20th.

The Croatian War of Independence—just one in a series of conflicts known as the Yugoslav Wars—ushered in a level of brutality not seen in Europe since World War II. Indeed, one reporter characterized it as “a war fed by centuries-old hostilities and carried out with a crude vigor reminiscent of the Middle Ages.” Almost 20,000 people would die by war’s end, while devastating attacks on Croatian infrastructure caused nearly $37 billion in damages. Phone lines were quickly cut down, mail services interrupted, and transportation between different regions became nigh impossible. As a consequence, Serbian fighters venturing behind Croatian lines had no way of contacting friends and family. The soldiers’ complaints did not concern military officials, given that satellite technology allowed for them to stay in contact with Belgrade’s military HQ.

An unorthodox approach emerged in Požarevac, an eastern Serbian city. Famous for its swift carrier pigeons, the city hosted many fanciers, such as Slobodan Brkić, the president of the country’s premier pigeon society. A lover of pigeons since he was 6 years old, Brkić specialized in breeding Tipplers, a breed renowned for its flight stamina. In 1975, he founded the first Tippler club in Yugoslavia, while in the 1980s, he helped organize the Yugoslav Carrier Pigeon Association. Inspired by accounts of pigeons delivering despatches during the Great War, Brkić opted to donate his club’s birds to soldiers traveling along the route from Požarevac to Vukovar, Croatia, the site of fierce fighting.

Beginning in Mid-October, Brkić started distributing Požarevac’s pigeons to local soldiers. They were placed in “ventilated cake boxes” and driven into Croatia along with other supplies, a journey which required “days of stealthy movement.” Handlers on the frontline received the pigeons and distributed them to Požarevac fighters, who were instructed to secure brief messages to the birds’ leg bands and release them. In a testament to the birds’ prowess, they typically made the return journey in around 1 to 2 hours. The first pigeon to return—a bird called Whitehead—brought news home that one soldier was safe and fighting in the Croatian town of Mirkovci. By the end of November, at least 90 successful deliveries had been completed. Only one bird had been lost on the frontline, a racing pigeon named Big Red. His owner chalked the loss up to foul play; he claimed either a trained hawk or a Croatian sniper was likely responsible.

As the notes arrived, they were broadcast over the airwaves for the community’s benefit. “We began by reading the messages over local radio, because people here had no word on their boys at the front,” Brkić explained to an American journalist. The letters usually contained just a few words—”Dear father: I’m fine. Don’t worry about me. I’ll be home soon. Dule,” is a typical example. In spite of their brevity, the despatches brought intense joy to local families, who thanked Brkić profusely. “People were so happy to hear from their sons that they would come up to me on the street and kiss my hand.”

At the start of 1992, the intensity of the conflict waned. A cease-fire was brokered on January 2nd, thereby abrogating the need for pigeons. Based upon our research, we at Pigeons of War believe that this was the last conflict in which combatants depended upon pigeons to carry important messages. Požarevac’s pigeons, therefore, deserve much respect for proving that pigeon posts are still a viable option even in the Information Age.

Sources:

- “Слободан Бркић: Лет Дуг Читав Живот.” Recnaroda, 5 Sept. 2020, recnaroda.co.rs/slobodan-brkic-let-dug-citav-zivot/.

- Williams, Carol J., “Communications: Carrier Pigeons Make Comeback in War,” The Los Angeles Times, available at https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1992-01-11-mn-1529-story.html

-

The Finnish Defence Forces’ Pigeon Service: 1923 – 1940s A.D.

Finland emerged as a latecomer to the pigeon arms race—while other countries had started supplying their militaries with pigeons in the late-1800s, it wasn’t until the 1920s that Finland implemented its own military pigeon service. This late start is unsurprising, as Finland was a possession of the Russian Empire from 1809 to 1917, known formally as the Grand Duchy of Finland. As a Russian territory, Finland lacked a separate army of its own after 1901. In the wake of the Russian revolution, however, Finland declared its independence on December 6, 1917.

A punishing civil war erupted in Finland throughout the first half of 1918, during which the nation’s newly minted military experienced multiple communication system breakdowns. In the aftermath of the war, Finnish military leaders looked abroad for ideas to bolster the military’s communications. In 1923, Major Leo Ekberg spent time in Denmark, observing his host country’s telecommunications units. He eventually was assigned to the Danish Army’s signal corps and learned of its pigeon program, becoming intimately acquainted with training techniques. Just a few months later, in the spring of 1924, Lieutenant Colonel and erstwhile trapshooter Unio Sarlin put his training for the summer Olympics on hold and traveled to Morocco for a similar mission. He was surprised to find that the Moroccan Army relied on pigeons even though radio, telephone, and telegraph equipment was readily available.

With these experiences under their belts, the Finnish officers decided it was time for their military to develop its own pigeon service. The Army obtained a small flock of pigeons for experimental purposes in 1923. The flock remained limited to just a few birds and was used on a trial basis for the next several years. In October 1927, however, the Royal Danish Army shipped 40 pigeons to Finland’s military, free of cost. Suddenly, the Army found itself with a rapidly-growing pigeon service. Sarlin assumed the mantle of leadership over the fledgling Finnish Pigeon Service (FPS). When the Danish pigeons arrived in Finland, they were assigned to a telecommunications unit in Riihimäki, which was commanded by Major Ekberg.

Ekberg possessed the requisite experience to get the FPS off the ground and it showed. The unit’s breeding program swiftly exceeded expectations; indeed, in the opening months of 1928, the military found itself with a pigeon surplus. Too many, in fact, for the Army to properly house. Although the Army had been experimenting with pigeons since at least 1923, the primary loft could hold approximately hundred birds—and that was if they were crammed in there tightly. To improve the pigeon service, Army officials contacted the Ministry of Defense and requested funds for building a larger coop. They had low expectations—such a request had been made annually since 1924, yet the Ministry never prioritized the FPS’ needs.

While the army’s petition for a bigger pigeon loft languished in limbo, FPS officers looked for places to put their birds in the interim. The White Guard, the country’s voluntary militia, expressed an interest in keeping some of the pigeons at its officers’ school in Tuulusa, while Ekberg thought that they might be useful at sites in eastern Finland, or in areas between the mainland and the outer islands to enhance coastal defense communications. The Ministry, nonetheless, ignored these proposals. Fed up with the agency’s intransigence, Ekberg told the Ministry bluntly that if it refused to build a larger coop for the military’s pigeons by 1930, then the pigeon service should be terminated, since no real support had been provided since its founding in 1923.

Ekberg’s tough tone with the Ministry worked—it quickly agreed to provide the FPS with more support. Over the next several years, the Ministry would work closely with Sarlin and Ekberg to develop a sophisticated military pigeon service. With the Ministry’s full support, the FPS once again looked abroad for inspiration. In 1930, the FPS received detailed information from their French counterparts about the French Army’s pigeon service. In 1931, FPS officials toured Germany’s pigeon stations for several weeks. The officials were awestruck at the amount of pigeon merely at the German Army’s central loft in Spandau, 1200. Encouraged by these trips, Sarlin planned further fact-finding missions to Sweden, Norway, and Estonia.

Armed with knowledge gleaned from some of the world’s preeminent military pigeon services, the FPS embarked on a series of projects. Permanent lofts were planned for military installations in Helsinki, Parola, Pori, Turku, Kangasa, Hämeenlinna, and Vyborg. FPS officials also wanted to develop improved training courses, import quality stock from Germany, and mobile lofts for use out in the field. It’s unclear from the record how many of these objectives were met.

Meanwhile, the army’s pigeon service expanded to other branches of Finland’s military. In August 1933, the Air Force received a pigeon station at the Suur-Merijoki airbase near Vyborg. The birds were to be used by pilots to communicate with the ground in lieu of radio, which still was not feasible for Finnish aircraft. That same year, the Navy received a batch of pigeons at its Maritime Defense headquarters in Helsinki. Naval officials wanted the birds for a special project: maintaining communication from submarines out at sea. Normally, a submarine could release pigeons upon surfacing, but such an option was not available to downed subs or when it was not safe to surface. To bring the pigeons from the sub to the surface, a torpedo was designed to be large enough for two military pigeons to fit inside. Ideally, upon being launched from the sub, the torpedo would rise to the surface and open up, allowing the pigeons to fly messages to the nearest naval facility. While this may seem a bit of a harebrained scheme to modern audiences, tests had demonstrated the torpedo was a safe and secure option for pigeons. Sarlin approved of these experiments, but it doesn’t appear the pigeon torpedo ever made it out of the experimental stage.

By 1935, the Finish military boasted 690 pigeons housed in lofts in Helsinki, Valkjärvi, Kiviniemi and Suur-Merijoki. These pigeons included both foreign strains and those supplied by a Finnish fancier group. As with other services, an issue frequently encountered was hawk and falcon attacks. In the fall of 1933, for example, peregrine falcons swooped in during a naval training session and killed half of the birds present. Avian tuberculosis was also a major threat, plaguing the military’s lofts. At the Kiviniemi loft, around 60 pigeons of Latvian stock were found to have tuberculosis. Other common diseases included proctitis, E. Coli, infectious rhinitis, and thrush. Finally, Finland’s extreme subarctic climate occasionally affected the birds’ performance.

In spite of the FPS’s best efforts, Finland’s military pigeon service began to lose steam in the mid-1930s, as improvements in radio technology pushed the pigeons to margins. In 1938, an internal assessment of the military’s communication sectors mentioned pigeons very little in comparison to radio units. The author recommended that the pigeons be given to the Army’s signal corps, from which they could be transported quickly to the front line by motor vehicles if necessary. Yet, when the Winter War started a year later, the birds were not incorporated into combat operations; an oversupply of Estonian field radios meant that the pigeons were no longer vital to the military’s interests. Near the end of World War II, the government slaughtered the birds and distributed the meat to injured soldiers in military hospitals. That was the death knell for the FPS—the Finnish military never worked with pigeons again.

In spite of its short existence and ignominious end, the FPS has managed to leave a footprint. The public can view exhibits dedicated to the FPS at the National Message Museum in Riihimäki and the Finnish Air Force Museum in Tikkakoski. The FPS has even inspired a modern work of fiction. Heli-Maija Heikkinen, a history lecturer and long-time admirer of the FPS, was dismayed that no stories of brave war pigeons had been preserved in the Finnish military archives. To remedy this, she wrote a novel in 2014, entitled Viestikyyhkyupseeri (The Carrier Pigeon Officer). Set during World War II, the book concerns Frans Jokimies, a pigeon trainer, breeder, and caretaker employed by the Finnish military. In September 1944, Frans receives an order from his superiors to slaughter the military’s birds. He cannot follow this unconscionable decree, so he and his wife Anja flee to Denmark with the pigeons in tow and remain there for decades. Amidst this backdrop, the author explores themes of war and sacrifice, forgiveness and relationships. It’s a worthy tribute to the FPS’ officers and pigeons and proof of their lasting legacy.

Sources:

- Karjalainen, Mikko, “Viestikyyhkyjä taivaalla,” Puolustusvoimien Kokeilutoiminta Vuosina 1918-1939, Vol. 1: 43, 2021, at 166, available at https://www.doria.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/180859/PVn_kokeilutoiminta_Karjalainen%20et%20al.%20%28verkko%29.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

- “Viestikyyhkyt Olivat Sota-Ajan Unohdettuja Sankareita.” Yle Uutiset, 27 Nov. 2014, yle.fi/a/3-7654835.

- Viestikyyhkyupseeri – Heli-Maija Heikkinen , kirja.elisa.fi/ekirja/viestikyyhkyupseeri.

- “Viestimuseo Muistaa Vainovalkeat Ja Kirjekyyhkyt.” Hämeen Sanomat, 14 June 2018, http://www.hameensanomat.fi/paikalliset/5147126.

-

“Very Gallant Gentlemen:” The Pigeons of the Royal Naval Air Service, 1916-1918 A.D.

The United Kingdom’s Royal Air Force (RAF) enjoys the honor of being the world’s first independent air force. For over 100 years, the RAF has protected Britain’s skies and air space from harm, playing a major role in the Second World War and the Cold War. Few people, however, are aware of the RAF’s predecessors during the First World War, the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) and the Royal Flying Corps, which merged in 1918. This week, we take a look at the RNAS and how it relied on pigeons during the Great War.

On July 1st, 1914, the Admiralty of the United Kingdom officially created the RNAS. Envisioned as the Royal Navy’s (RN) analogue to the Army’s Royal Flying Corps, the RNAS had three primary objectives: maritime reconnaissance, patrolling for enemy ships and U-boats, and attacking enemy coastal territory. The newly formed unit assumed ownership over “[a]ll seaplanes, aeroplanes, airships, seaplane ships, balloons, kites, and any other type of aircraft that may from time to time be employed for naval purposes.” All naval personnel with aircraft experience, both active and reserve, were immediately reassigned to the RNAS. Within just a few weeks, the RNAS boasted 93 aircraft, six airships, two balloons, and 727 officers and enlisted men.

Barely a month after its launch, the RNAS found itself preparing to take part in the largest European engagement since the days of Napoleon. After several weeks of fighting, an opportunity emerged for the RNAS to test its reconnaissance and offensive capabilities. Military officials wanted to bombard the Imperial German Navy’s airship bases on the Heligoland Bight, a bay within the North Sea, to prevent future zeppelin attacks on the British mainland. But the bases were out of range for British-based aircraft, so a crew from the RNAS was recruited to aerially reconnoiter the Heligoland Bight and bomb any zeppelin sheds spotted in the vicinity. On Christmas morning 1914, seven RNAS seaplanes took off from a group of seaplane tenders stationed near the bay. The seaplanes flew for over three hours, surveying the area and bombing a few minor shore installations. Although the results obtained by the RNAS were meager, the Raid on Cuxhaven—as it came to be known—demonstrated the potential of a unified sea-and-air attack.

The RNAS also spent considerable time patrolling for enemy U-boats, which were sinking thousands of merchant ships bound for French and British ports. Over the course of the war, the RNAS searched over 4,000 square miles in the North Sea, the English Channel, and along the coast of Gibraltar for submarines. Although the seaplanes’ guns generally weren’t sufficient to sink submarines—only one German U-boat was sunk by a British plane unassisted by warships during the conflict—the pilots could relay the subs’ locations to the RN’s surface fleet.

An issue frequently encountered in the RNAS was how to communicate with pilots who were stranded in the sea. Seaplanes and flying boats were too small to accommodate a wireless set until 1917. Even after the planes received wireless units, the devices were useless in the event of engine failure. As readers of this blog will recognize, this is the exact emergency scenario for which a pigeon service is ideal. But the RN had phased out its pigeons in 1908, viewing the birds as antiquated with the rise of wireless telegraphy. RNAS officials were inspired to reinstitute a naval pigeon service following an episode involving their French counterparts. On June 8th, 1916, an injured pigeon arrived at Saint-Pol-sur-Mer bearing a message from a downed seaplane near Ostend and Zeebrugge along the Belgian coast. A French destroyer traveled to the crash site, only to encounter a German torpedo boat attempting to haul the seaplane away. A skirmish broke out and the seaplane was ultimately lost.

Even though the French had failed to recover the seaplane, a British RNAS station in Dunkirk learned of this episode and was impressed with its results. An inquiry led to the donation of a few well-trained birds, which were rapidly put to use. Just two days later, two RNAS seaplanes flying 4,000 feet over Zeebrugge released pigeons with accompanying despatches revealing the area was enemy free. The pigeons successfully returned to their Dunkirk lofts bearing good tidings. On June 20th and 24th, pigeons brought news to Dunkirk of shot-down RNAS seaplanes, facilitating their rescues.

With such an auspicious start, it soon became standard operating procedure for each RNAS flight crew to carry a basket of pigeons with them on every journey. Writing nearly 90 years later, Henry Allingham—the last surviving veteran of the RNAS—explained the process:

[W]e didn’t have radio. We had pigeons which we carried in a basket. . . . Some of our people who were adrift in the drink could be there for up to five days, and they used to let the pigeons go. They would fly back to the loft at the station, and a search party would be sent out to look for them. As a general rule, after five days of searching, they’d give up and the men were lost.

RNAS pilots and observers received specialized training from pigeon experts before they ever handled a bird. It was especially important that they be instructed on how to avoid harming pigeons during aerial releases. “The liberation of a pigeon from a seaplane in flight requires a certain amount of dexterity,” remarked one contemporary publication, “as the bird is liable to be caught in the slip-stream of the airscrew and dashed against the tail group.”

The RNAS maintained flocks of pigeons at the principal naval air stations on the mainland. Although the RNAS owned some 1,000 birds outright, it also received three thousand birds from donors as diverse as King George V. When released at sea, the donated pigeons flew back to the original owners home, where the owner would telegraph the message’s contents to the proper authorities. The bird would eventually be returned to the nearest RNAS station and reunited with its crew. Until then, the owner was expected to feed and care for the bird without compensation from the RNAS.

The RNAS’s pigeon program was wildly successful. In spring 1918, it was claimed that RNAS pigeons had carried over 1500 messages. Newspaper accounts regaled audiences with tales of pigeons saving RNAS servicemembers from watery graves. In one widely reported story, a seaplane pilot, forced to make an emergency landing off the coast of Kent, released a pigeon at 7:24 a.m. The bird returned to its loft by 8:00 a.m. and a trawler was enroute within 30 minutes to rescue the pilot. An even more impressive feat occurred when four pigeons arrived at a station one after the other, telling the story of a fierce dogfight over the North Sea fragment-by-fragment. However, sometimes the news brought back via pigeon wasn’t pleasant. Once, a pigeon returned with a message written in German declaring that the RNAS pilot and seaplane had been captured.

The most famous story of a rescue by an RNAS pigeon occurred on September 5th, 1917. That morning, two RNAS planes flew out of the Yarmouth naval air station, heading toward the North Sea. They were in search of German zeppelins, which had been operating near Terschelling Island, north of the Netherlands. A total of six men were present: four in a seaplane and two in a biplane. Halfway into the flight, they spotted two zeppelins and opened fire. The dirigibles attained the upper-hand, riddling the English planes with bullets, while German ships fired anti-aircraft shells from below. As the Germans left the scene, the biplane plummeted into the ocean, its engine destroyed. The seaplane was still airborne, though it suffered from a broken wing and a misfiring engine. It landed near the biplane and its crew brought the two men aboard. Although the six men were unharmed, the seaplane failed to become airborne after repeated attempts. They opted to release four pigeons over three days with news of their calamity. Only one pigeon managed to make the 50-mile flight back to the Norfolk coast, Pigeon N.U.R.P/17/F.16331, but it died immediately from exhaustion. Reading its message, naval officials learned of the men’s location and rescued them; not a single life had been lost thanks to the pigeon’s sacrifice.

At its peak, the RNAS comprised 55,066 personnel, 2,949 aircraft, 103 airships and 126 coastal stations. Yet, by 1918, British war planners were keen to consolidate the nation’s military aircraft and personnel under one branch. On April 1, 1918, the RNAS merged with the Royal Flying Corps to become the RAF. The contributions of the RNAS’ birds weren’t forgotten, however. In November 1918, 13 former RNAS birds were displayed at a London event; between all of them, they had saved a dozen lives and many downed aircrafts. In April 1919, the RAF issued an official list of pigeons who had distinguished themselves in wartime service on flying boat and seaplane operations. Meanwhile, Pigeon N.U.R.P/17/F.16331 was preserved in a glass case bearing the inscription, “A Very Gallant Gentleman;” it can still be seen to this day at the UK’s RAF Museum.

Sources:

- Flying Boats over the North Sea.” RAF Museum, 1 Feb. 2021, https://www.rafmuseum.org.uk/blog/flying-boats-over-the-north-sea/;

- Milford, Humphrey, The Periodical, Vol. 13, No. 145, June 15, 1928, at 75.

- O’Flaherty, Patrick, “Peaceful Pigeons in Modern Warfare,” The Montreal Star, Mar. 2, 1918, at 17.

- “Pigeons Bring Help to Our Fighting Men,” The Buffalo News, Sep. 26, 1919, at 19.

- “R.A.F. Pigeon Service,” The Aeroplane, Vol. 16, No. 2, Jan. 15, 1919, at 306.

- “Royal Naval Air Service,” Flight, Vol. 6, No. 26, June 26, 1914, at 686-89.

- Simkin, John. Royal Naval Air Service. Spartacus Educational, https://spartacus-educational.com/FWWrnas.htm.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence, The Great War at Sea, at 264 (2014).

- “The Gallant Pigeon That Saved Six WW1 Airmen Lost in the North Sea.” Look and Learn, 30 May 2012, https://www.lookandlearn.com/blog/18494/the-gallant-pigeon-that-.

- “Wireless Signals,” The Nottingham Evening Post, Feb. 4, 1908, at 3.

- “WW1 Flying Boat Crew.” RAF Museum, 1 Feb. 2021, https://www.rafmuseum.org.uk/blog/ww1-flying-boat-crew/.

-

The Martyrs of Nomain: A Tale of Pigeons and Spycraft During the Great War

For all practical purposes, the Great War began when Germany invaded Belgium on August 4th, 1914. Despite the valiant efforts of the Belgian Army, it was an unfair fight and the small country was quickly overrun. For the duration of the war, German military authorities occupied nearly the entire territory. This is common knowledge, yet many popular histories of the conflict neglect the German occupation of northeast France during this period. Indeed, by November, Germany had gained a foothold in ten French departments, the most populous of which was the Nord Department. This week, we take a look at four brave residents of the Nord who were executed for engaging in clandestine pigeon networks.

At the close of 1914, over 1 million French residents in the Nord Department found themselves under German occupation. Naturally, the presence of a foreign army in their homeland triggered active resistance movements, as in Belgium and Luxembourg. Espionage emerged as a powerful form of undermining German authority; Nordistes were all too eager to provide Allied secret services with enemy intelligence. While men and women bravely volunteered their services and passed on info to secret agents in person, others opted to use pigeons to send clandestine information back to the Allies. This is unsurprising—pigeon keeping was a popular pastime in the Nord region, with over 20,000 members enrolled in a regional club.

But pigeons were in short supply throughout the Nord; the German military government had ordered their destruction in October 1914 to prevent communication with the Allies. To provide Nordistes with much-needed pigeons, in March 1917, British intelligence started airdropping pigeons via balloon or plane into occupied France. Attached to a parachute, the pigeon floated down into a meadow or field, waiting for a Nordiste to find it. In the event someone found the bird, they’d notice a detailed questionnaire attached to the its leg. It was hoped that patriotic individuals would look over the questionnaire and reveal important details about German military units and movements. A set of instructions cautioned participants to disguise their handwriting and not to include their real names or addresses in case Germans intercepted the bird. This was a necessary measure, in light of French patriotism. “[T]he French people are fond of glory,” a French partisan warned a British intelligence official, “and unless they are warned, I am afraid some of them will be sticking their names to the bottom of the message just to show how they are trying to help their country.”

Getting the pigeon behind enemy lines was the simple part. Nordistes took a huge risk if they decided to use the airdropped bird for espionage. Those who had a pigeon in their possession had to be extra cautious that no one actually saw the bird. “Keeping them . . . without arousing the suspicion of the Germans or the curiosity of inquisitive neighbors, proved too great a difficulty,” British intelligence officer Henry Landau reflected in a post-war memoir of his espionage activities. If a person did send vital information, Germans might intercept the pigeon and discover his or her identity. Finally, sometimes the Germans themselves planted one of their own pigeons for unsuspecting Nordistes to find. Any info sent by that bird would end up in German lofts.

Still, those bold enough to try this venture occasionally passed on intelligence of real value to Allied officials. In May 1917, for instance, several individuals sent via pigeon the location of several ammunition depots and three big enemy guns in Cambrais. A few days later, French planes bombed the depots and two of the big guns. For this reason, German military authorities took a draconian stance against the use of pigeons for espionage. Anyone found in possession of a pigeon or identified in an intercepted despatch faced immediate arrest, followed by a trial before military tribunals. In the event of a conviction, execution by firing squad was the usual penalty.

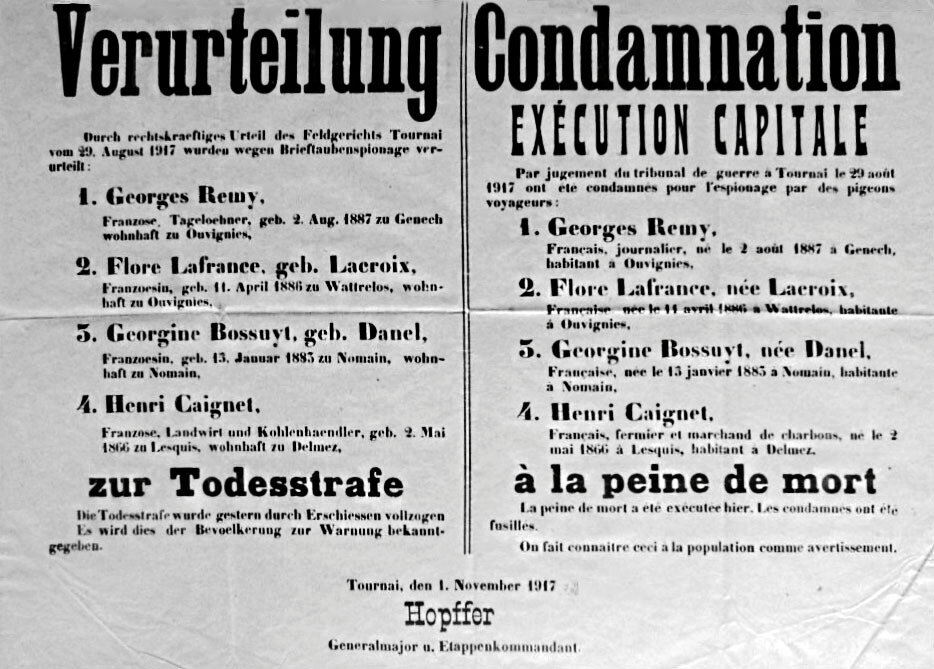

It is in this milieu that we encounter the subjects of our story. In April 1917, a German soldier stationed in Lens, Belgium shoots down a pigeon in flight. He quickly discovers it’s a spy pigeon when he sees a filled-out questionnaire attached to its leg. In looking over the questionnaire, he realizes that an active spy ring exists in Nomain, a town in the Nord. Three names appear in the document, all residents of Nomain: Georges Rémy, a railway worker, Henri Caignet, a coal merchant, and Flore LaFrance, a young mother. The German authorities swiftly arrest these individuals and their spouses and transport them to Tournai, Belgium. An investigation into the matter implicates several other collaborators, including Georgine Bossuyt; like LaFrance, she, too, is a mother of young children.

On August 4th, the accused appear before a war tribunal in Antwerp. Following the hearings, the tribunal sentences Rémy, Caignet, LaFrance, and Bossuyt to death; their spouses and other collaborators receive decade-long prison terms instead. Although the condemned file appeals of their sentences, their petition is denied in September. They’re sent back to the Tournai Citadel to await execution by firing squad. They don’t know when it will happen. In the meantime, Rémy’s wife gives birth to a daughter; she names her Georgette.

On October 31st, the collaborators are informed at 11:00 am that they will be shot at 5:00 pm. They are granted just two hours to gather with their families in a makeshift chapel and say goodbye. Eyewitness accounts paint a heart wrenching picture of these last moments. LaFrance cradles Rémy’s newborn daughter as he embraces his wife. Caignet kisses his daughter Yvonne, letting her know that he is to be shot that evening. Bossuyt bids her husband farewell, but is not allowed to see her children—they are too young and left with some of the Citadel’s nuns. An hour before the sentence is to be carried out, the families depart. A final mass for the condemned is held where they receive communion.

As five o’clock draws near, the condemned are brought to the execution site. Rémy’s legs give out and he is dragged along by two burly soldiers. Meanwhile, the women put on a brave show. Bossuyt and LaFrance—sporting cockades emblazoned with France’s national colors—vigorously refuse to be blindfolded. Each prisoner is tied to a post. The women shout “Vive La France!” for their final words. As the soldiers prepare to fire, one refuses to shoot. He is quickly replaced and the firing commences. The women are shot first and their bodies placed in coffins, but it is immediately apparent to all that Bossuyt is still breathing. She is pulled halfway out of the coffin and shot again. A priest breaks down in tears as he blesses the women’s bodies. The men are shot next without incident. The bodies are buried onsite in a mass grave before nightfall.

German authorities are confident these executions will serve as a deterrent. But they’re wrong. In spite of German threats, collaborators continue using pigeons to communicate with the Allies throughout 1917 and 1918. By war’s end, nearly 40% of the questionnaires provided by the British have returned via pigeon, beating internal estimates that only 5% would return.

The story of Nomain’s martyrs received much attention in the years following the war. Two monuments were publicly dedicated to them during the Interwar period: the Monument aux Morts in Nomain and the Monument de la caserne Ruquoy in Tournai. In the 1920s, the French government posthumously awarded each individual the Legion d’honneur, the country’s highest order of merit. Even 100 years later, their story occasionally surfaces in French and Belgian media.

This grim chapter reminds us of the harsh realities of war. In using pigeons to send confidential information to the Allies, the martyrs of Nomain took major risks and it cost them dearly—not only did they lose their lives, their children grew up without them. And yet they took these chances, motivated by a love for France that transcended self. We at Pigeons of War salute these courageous individuals for making the ultimate sacrifice to aid the Allied cause.

Sources

- Bausiers, Christian. “Les Patriotes Fusillés, Héros Méconnus.” Skyrock, 9 Feb. 2013, https://edidep.skyrock.com/3142180984-CONNAITRE-TOURNAI-SON-HISTOIRE-SES-REALISATIONS-SES-PROJETS.html.

- Connolly, James E., The Experience of Occupation in the Nord, 1914-18, at 8, 12, 15, 266-69 (2018).

- Département: 59 – Nord, https://www.memorialgenweb.org/memorial3/html/fr/resultcommune.php?idsource=30202&dpt=59

- Landau, Henry, All’s Fair: The Story of the British Secret Service Behind the German Lines, at 81 (1934).

- Thuliez, Louise, Condemned to Death, at 45-46 (1934)

-

The Kingdom of Serbia’s Pigeon Stations: 1908 – 1918 A.D.

The Balkan Peninsula was a hotbed of activity during the latter-half of the 19th century. The Ottoman Empire had ruled the region for centuries, but a rise in ethnic nationalism challenged the status quo. Following a series of wars and rebellions, the Sick Man of Europe gradually receded from the Peninsula. At the close of the century, three newly independent countries existed in the Balkans: The Kingdom of Serbia; the Principality of Montenegro; and the Kingdom of Romania. This week, we take a look at the Kingdom of Serbia and its military pigeon service.

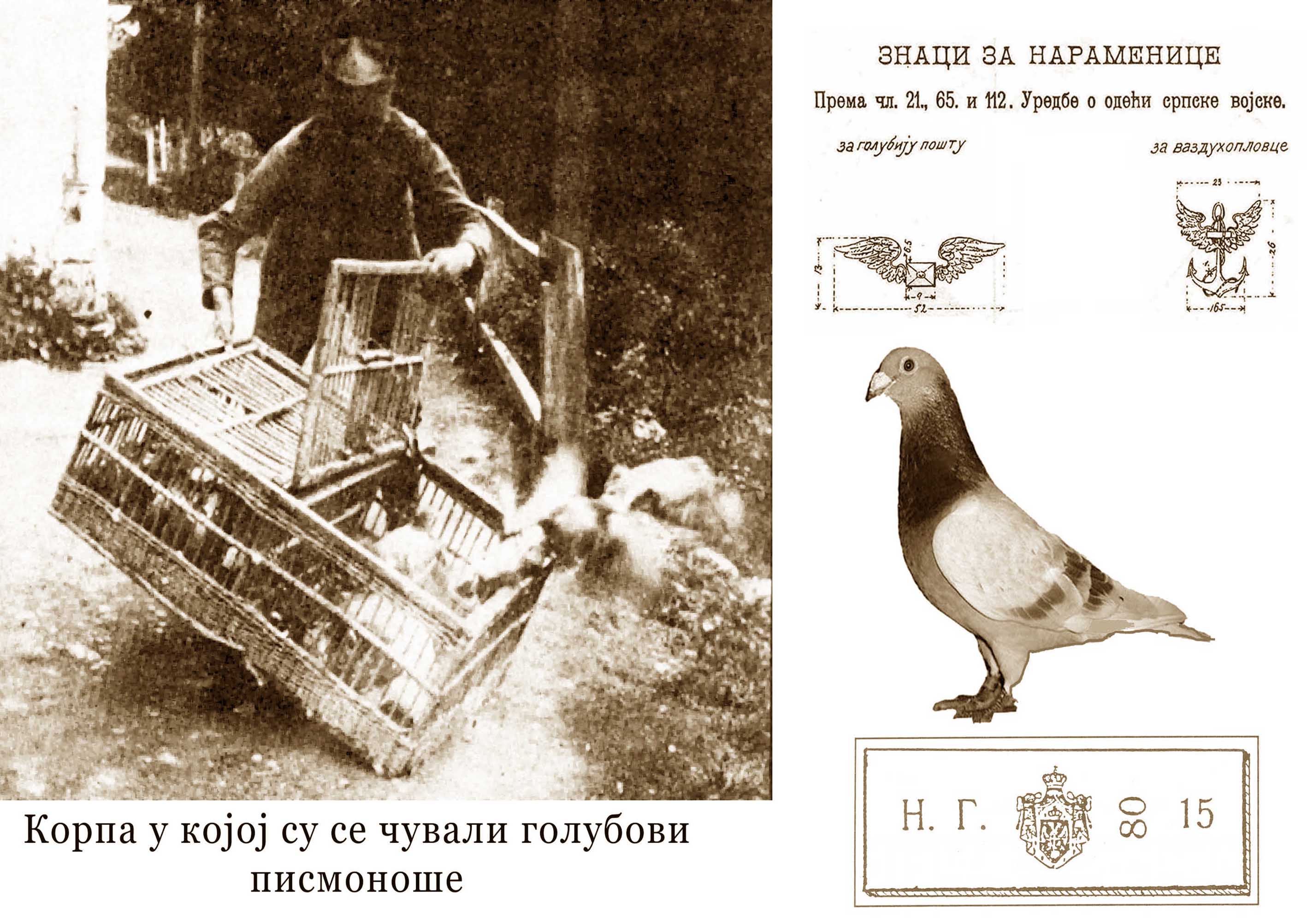

The Kingdom of Serbia implemented a military pigeon service in the opening years of the 20th century. The service was the brainchild of Kosta Miletić, an innovator of military aviation and the first Serbian Air Force Commander. As a young army officer, Miletić had been sent to a Russian military aviation school in 1901. At that time, military aircraft were limited primarily to gas-filled observation balloons, which had been deployed in the American Civil War and Franco-Prussian War to great effect. Throughout 1901 and 1902, Miletić studied up on the art of military ballooning, achieving excellent grades. He also spent six months at the school’s pigeon station, where he learned that the birds could be used by balloon pilots to send status reports to troops on the ground. In September 1902, Miletić had the opportunity of putting his ballooning and pigeon training in action. The Russian Army had planned a series of grand maneuvers across the country and Miletić was assigned to the Kiev Army. Piloting a balloon, he attained a height of 1100 meters and a distance of 180 kilometers, all the while sending messages back to the ground via pigeon.

Miletić returned to Serbia as the country’s first aeronaut The Minister of Defense assigned him to work in the Ministry’s engineering department, where he developed plans for balloon units in the Army. Inspired by Russia’s pigeon stations, he also sketched out concepts for a network of pigeon stations across Serbia. However, when Miletić presented his ideas to the Minister, the plans were shelved and Miletić reassigned to a different division.

Miletić’s plans for a military pigeon network remained dormant until October 1908, when Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina During that crisis, a basket of 17 carrier pigeons en route to Obrenovac was seized by the Serbian authorities. The Minister of Military Affairs sent Miletić to receive the pigeons and he determined that they were from Austro-Hungarian pigeon stations, having been brought to Serbia to assist Austro-Hungarian spies. Almost immediately, the military ordered Miletić to set up a pigeon station in Niš.

On November 26, 1908, the Niš station was established, stocked with mostly confiscated Austro-Hungarian pigeons. Under the care of an engineering battalion, the station was led by a lieutenant who had been personally trained by Miletić. The staff included a sergeant and three soldiers. A horse-drawn cart was used to transport the birds. In 1909, an additional building was constructed to meet the station’s needs—it contained an office, a soldier’s room, a storehouse for food, and a section for ill pigeons. Actual flight training did not take place until 1910, after the foreign birds had produced a sufficient quantity of squeakers. The pigeons were trained to fly from Sukovo, Užice and Smederevska Palanka. From Sukovo, the pigeons could reach Niš in one hour, while from Smederevska Palanka and Užice, they made the trip in two hours.

Officials were impressed with the results obtained at Niš. In 1911, they ordered that a second station be built in Pirot. The pigeons at this station maintained communications between Pirot and other military fortifications in the area. On Christmas Eve 1912, the Ministry of Defense officially established the Serbian Air Force (SAF) as a division within the Army, becoming one of the first countries to boast its own air force. The fledgling SAF consisted of the military’s twelve airplanes, two balloons, a hydrogen plant, and two pigeon stations. Miletić assumed command, a natural choice given his background. Plans were made to expand the Niš station by adding two more lofts and a breeding depot to supply Pirot and future stations. However, it is unclear if these changes were ever implemented.

An opportunity to test the SAF’s pigeons under wartime conditions appeared in 1913, when Serbia was engaged in the First Balkan War. For some unknown reason, though, the Serbian military did not use its birds during that conflict, despite their availability. Another opportunity emerged a year later, as Austria-Hungary prepared to invade Serbia for the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The SAF put its 192 pigeons to work in the opening weeks of the war, flying messages from border troops to the Supreme Command of the Army, which was based in Niš.

But the combined might of the German, Austro-Hungarian, and Bulgarian armies overpowered the Serbian Army. On November 23rd, 1915, the Serbian government and Supreme Command ordered soldiers to retreat across the mountains of Montenegro and Albania to the Adriatic coast. The Niš and Pirot stations were evacuated, as the staff members and the pigeons joined the retreat. By February 1916, most of the remaining Serbian troops and government officials had been evacuated to the Greek island of Corfu, then under French control.

Amidst this retreat, military officials paused the pigeon post indefinitely as the Army regrouped. Near the end of 1916, the Serbian Army traveled to Thessaloniki to join in the Allied effort to defeat Bulgaria. After months of fighting, on August 15, 1918, the Supreme Command reactivated the military’s pigeon service, placing it under the ambit of the Army’s postal and telegraph department. Officials opted to set up a pigeon station in Stari Čardak, a city near Thessaloniki. Lieutenant-General George Milne, commander of the British Salonika Force, generously donated 150 pigeons and two lofts to get the station up and running. The pigeons apparently greatly contributed to Allied intelligence work on the Macedonian Front; Allied agents took the birds with them as they ventured into enemy territory.

The Great War ended in the fall of 1918. Although it was one of the victors, the Kingdom of Serbia ceased to be a political entity that year. In its place emerged the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. A nation-state embracing the ideology of Pan-Slavism, the country eventually changed its name to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929. In spite of the political change, the military wasn’t ready to jettison its birds. The Yugoslav Army maintained a pigeon service in the inter-war period, even expanding it; a prominent station housing 2,000 birds was established at Petrovaradin. After the Second World War, the military abandoned its pigeon service, but pigeons still played a role in the Yugoslav Wars in the early 1990s. It is a testament to Kosta Miletić’s vision that Serbia’s military pigeon service lasted in one shape or form for decades.

Sources:

- “110 Година Голубије Поште у Српској Војсци.” 110 Година Голубије Поште у Српској Војсци | УПВЛПС, https://udruzenjepvlps-org.translate.goog/blog/2018/11/02/110-godina-golubije-poste-u-srpskoj-vojsci/?_x_tr_sch=http&_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=wapp.

- Весна Илић, РТС. “Српско Војно Ваздухопловство На Данашњи Дан Формирано у Нишу.” Јужна Србија Инфо, 24 Dec. 2015, https://www-juznasrbija-info.translate.goog/drustvo/srpsko-vojno-vazduhoplovstvo-na-danasnji-dan-formirano-u-nisu.html?_x_tr_sl=sr&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=wapp.

- Benitez, E.M., “Military News Around the World,” The Command and General Staff School Military Review, Vol. XIX, No. 73, June 1939, at 27.

- Војска Краљевине Србије, https://www-pogledi-rs.translate.goog/forum/thread-4160-post-121406.html?_x_tr_sl=de&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=wapp.

- Lyon, James, Serbia and the Balkan Front, 1914: The Outbreak of the Great War, at 82-83, (2015).

- “‘The ‘Heavenly Army’ Flew from Petrovaradin up to 100 Kilometers per Hour, Did You Know about the Pigeon Post Unit?” Serbia Posts English, Serbia Posts English, 12 Nov. 2022, https://serbia.postsen.com/local/78284/The-Heavenly-Army-flew-from-Petrovaradin-up-to-100-kilometers-per-hour-did-you-know-about-the-PIGEON-POST-unit.html.

- Vojinović, Vladeta D., Vazduhoplovstvo Srbije na Slounskom frontu: 1916-1918, at 240 (2000).

-

Pigeons in the Third Crusade: The Siege of Acre (1189 – 1191 A.D.)

On May 11, 1189 A.D., Frederick I, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, sailed from Regensburg with an army of over ten thousand. Traveling to the Levant, they would soon be joined by Philip II of France and Richard I of England and their respective armies. For the third time within a century, Europe had rallied to reclaim the Holy Land for Christendom.

The First Crusade (1096-99 A.D.) had drastically changed the landscape of the Levant, with the European invaders–known as Franks to the local Arab populations–establishing 4 states: the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the County of Edessa, the Principality of Antioch, and the County of Tripoli. But in 1144 A.D., the County of Edessa fell to Zengi, the Turkmen atabeg of Mosul and Aleppo, spurring on the Second Crusade. The Franks failed to re-take Edessa, and in the intervening years Zengi’s son, Nur ad-Din, unified all of Syria under his control. In the fall of 1187 A.D., Saladin, the Kurdish successor to Nur ad-Din, seized both Jerusalem and the pivotal port city of Acre from the Franks. In response, Pope Gregory VIII issued a papal bull calling for another crusade.

In preparing to invade the Holy Land, the Crusaders likely gave little thought to the area’s communication networks. In fact, a sophisticated pigeon post had existed throughout northern Africa and southwestern Asia for centuries. This is not entirely surprising, as the pigeon was most likely domesticated in these areas. Intimately acquainted with the pigeons’ homing ability, trainers soon learned that pigeons could “cover the distance of twenty days’ walking in less than a day.” The first organized pigeon post in the Muslim world was established during the reign of the third Abbasid Caliph, al-Mahdi, in the late 8th century. At the Abbasid Caliphate’s peak, a series of government-run pigeon stations linked disparate provinces throughout the Empire. At each station, a chief of the dovecote oversaw general operations, supported by a guardian that cared for the birds and kept an eye out for returning flights. A secretary composed the messages, while another station employee tied the message to the pigeon and released it. Other employees exchanged birds with nearby stations to ensure two-way communication. Servants cleaned up the cages in exchange for the valuable guano, which they sold to farmers.

With this pigeon network, messages could be sent over a vast expanse of territory at speeds ranging from 30 to 60 mph. The Egyptian Arab historian al-Maqrizi records a humorous anecdote from the 10th century that illustrates the network’s efficiency. The fifth Fatimid Caliph al-Aziz loved cherries from Baalbek, Lebanon and wished to have some for dinner. Unfortunately for his appetite, he lived in North Africa. His ministers arranged for 600 pigeons to fly from Baalbek to Cairo with each bird carrying a small sack with a single cherry for the Caliph. Flying over 400 miles, these birds delivered the first cargo via airmail in recorded history.

By the time of the First and Second Crusades, the grand pigeon post of the Abbasids had declined considerably, but pigeons were still being used to convey information swiftly and reliably. The invading Europeans, in contrast, had very little experience with homing pigeons, and thus, were limited to sending messages at the speed of horses and runners. They soon found that the Muslim forces had an advantage over them. Arab scouts out in the field would monitor the movements of Frankish soldiers and send that information to their military leaders. Nevertheless, the fact that pigeons can be intercepted was exploited by the Franks during the Siege of Jerusalem in 1099 A.D. A pigeon flying towards the city was shot down by them. Its message revealed that reinforcements were heading that way, prompting the Franks to speed up their ultimately successful efforts to conquer the city.

In the decades prior to the Third Crusade, a systematic pigeon post re-emerged in the Muslim states. In 1171 A.D., Nur al-Din ordered that pigeon stations be set up across his territory, which stretched from the Sinai Peninsula to the border of modern-day Iran. His motivation for this order was to protect his border cities, which were frequently attacked by Franks. Reports of these skirmishes reached Nur al-Din well after the fact, leaving him unable to provide assistance. After the stations were set up in cities across his Empire, these reports reached Nur al-Din the same day. He was able to send military instructions to troops stationed near the border in real time, allowing his troops to mount a surprise counter-offensive against the Franks. Eventually, a regular service was implemented between Egypt and Syria.

Meanwhile, as the Kings of England, France, and the Holy Roman Empire marched toward the Levant, Guy of Lusignan, the ousted King of Jerusalem, decided to attack the city of Acre in the summer of 1189 A.D. It would not be an easy task. The city was well fortified—its east side lay within a walled peninsula in the Gulf of Haifa, while the west and south sides were protected by strong barriers. Several thousands troops defended the city, as it was one of Saladin’s primary garrisons and arms depots. Gathering 7,000 soldiers and 400 knights, Guy initially tried to breach the walls, but failed to break through. Knowing that thousands of European Crusaders would soon be arriving, Guy set up a camp outside the city and played the waiting game.

In the interim, the Franks attempted to starve Acre into submission. A series of 2-mile long trenches encircling the city and a naval blockade prevented supplies and information from easily reaching the besieged. Despite these efforts, Acre’s pigeon keepers and Saladin’s troops had exchanged birds at some point prior to the siege, ensuring that two-way communication with each other would be possible. Arab historian Imad ad-Din—who had accompanied Saladin during this period—notes that one of Saladin’s soldiers had provided the city with trained birds and had even built a large loft of reeds near Saladin’s pavilion to house the pigeons. A cipher was developed to prevent the Franks from reading any messages that were intercepted. Thanks to these pigeons, Saladin learned of the city’s struggles, allowing him to provide the assistance that was needed. Frequently, Saladin sent information or provisions into Acre by small boats or divers coming in through the harbor—to let Saladin know of their arrival, a pigeon was released. The pigeons also brought news from Saladin of his battles against the Crusaders, giving the city hope. For their part, the pigeon served admirably. Imad al-Din had nothing but the highest praise for them:

These birds kept secrets loyally. They ensured the flow of information, guarded the letters jealousy, showed themselves as generous as the best of noblemen. They braved dangers, never made a mistake, and were prized as precious possessions,

Nevertheless, the city could hold out for only so long. As the siege wore on, thousands of European soldiers joined Guy’s army. In the spring and summer of 1191 A.D., King Richard and King Philip arrived at Acre, absent Emperor Frederick, who had drowned in the Saleph River while traveling through Asia Minor. Bringing much needed men and siege engines, the Kings’ presence on the battlefield tilted the siege in favor of the Crusaders. In July, the siege engines broke through Acre’s walls. Knowing that they were facing defeat, city officials wrote the following message and sent it to Saladin via pigeon:

We are so utterly reduced and exhausted that we have no choice but to surrender the city. If you do not effect anything for our rescue, we shall offer to capitulate and make no condition but that we receive our lives.

Saladin sent another pigeon in response, assuring them help would be forthcoming. But it was too little too late. The city officially surrendered on July 13th. Over time, Acre would become the new capital of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, remaining under Crusader control for another century.

The Third Crusade ultimately ended in a draw. The Crusaders failed to regain Jerusalem, but kept control of territory in Palestine. The Muslims destabilized the Christian kingdoms, but failed to drive the Franks out of the Holy Land. As for the pigeon post, it would continue under Saladin’s successors, the Ayyubids, reaching its greatest heights in the 13th century after the Mamluks came into power. But that’s a story for another day.

Sources:

- Allatt, H. T. W., “The Use of Pigeons as Messengers in War and the Military Pigeon Systems of Europe,” Journal of the Royal United Service, at 111 (1888).

- Gibbon, Edward, The Crusades, at 67 (1870).

- Hillenbrand, Carole, The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives, at 547-48 (2000).

- James, Peter & Thorpe, Nick, Ancient Inventions, at 526-27 (1994).

- Kistler, John M., Animals in the Military: From Hannibal’s Elephants to the Dolphins of the U.S. Navy,

- Lyons, Malcolm C. & D.E.P. Jackson, Saladin: The Politics of the Holy War, at 310 (1982).

- Kociejowski, Marius, The Pigeon Wars of Damascus (2011).

- Man, John, Saladin: The Sultan Who Vanquished the Crusaders and Built an Islamic Empire, at 44-46 (2016).

- Reston, James, Jr., “Warriors of God,” at 177, 198 (2001).

-

The Military Heritage of Venice’s Pigeons

Venice is famous for its pigeons. They’re everywhere, and tourists expect to see them. A special haven for Venice’s pigeons is Piazza San Marco, the city’s principal public square. Before the 20th century, San Marco’s pigeons were highly regarded, even considered sacred. Several origin stories have been advanced for these pigeons, but, for our purposes, we at Pigeons of War favor one legend attributing a martial heritage to these birds. The most detailed account of this myth has been reproduced below:

On the heels of the Fourth Crusade, the Republic of Venice purchased the island of Crete from Boniface, the Marquis of Montferrat, in 1204 after promising to support his acquisition of the Kingdom of Thessalonica. Not everyone was happy with this transition. Some of the native population in Candia, the island’s most important port, resisted their new overlords. Raniero Dandolo, son of the Venetian Doge Enrico Dandolo and an Admiral of the Venetian fleet, initiated a blockade of Candia in response. The blockade was supported by a Genoese fleet under the command of Enrico Pescatore, the Count of Malta. Long-time rivals, Venice and Genoa were ostensibly allies at this point. Yet, some of Dandolo’s officers noticed that a flock of pigeons were flying towards the Genoese ships. Intrigued, Dandolo ordered for some of the pigeons to be captured the next time they flew in that direction. When they appeared again, Dandolo’s men shot down 7 or 8 of them with arrows. Upon inspection, each pigeon had a letter from the Candiotes to the Genoese secured to its wing.

Dandolo stormed Candia the next night, driving out the Genoese. Soon, he had control of the whole island. While exploring the now vacant governor’s palace, the Venetians found a number of pigeons. Dandolo shipped them to Venice with news of his victory. Grateful for the role the pigeons played in Dandolo’s conquest, city officials treated the birds with great honor, allowing them to dwell at Piazza San Marco.

Over time, San Marco’s flock of pigeons multiplied into an enormous colony. A 19th century tourist described their dominion over the Piazza and the city at large:

They rest at night in the laces of the palaces and the cornices of the great cathedral, on triumphant columns and arches and in the airy arcades of the Campaniles. They nestle with the winged lions and dart noiselessly through the churches. They brush the sacred altars and the tombs of kings and doges and bishops. They walk the marble pavements in groups and in hundreds, unmolested among throngs of passers. They play with the children and fly up on your cafe table for their share of the cake or water.

Undoubtedly, this increase was facilitated by a religious tradition dating back to the Middle Ages. Every Palm Sunday, the priests of San Marco released imported pigeons with weights tied to their wings over the Piazza. An Easter gift from the Doge to his citizens, most of those birds were easily caught by Venetians and eaten. The few survivors, however, were allowed to reside at San Marco, as they were believed to have earned the protection of the saint. After centuries of cross-breeding, the pigeons had developed into a stunning bird by the 19th century. One observer described their traits in almost rhapsodic terms:

[They] are black, and white (or grey) with pink eyes and red feet. A beautiful green collaret surrounds the throat; the body is quite white under the wings. Some of them have white tails; whiter than the snow which falls on the summit of the Apennines; and opal or topaz eyes, which change their tints a thousand times a day.

Meanwhile, the city’s generosity toward the Piazza’s pigeons persisted. Every day at 2 pm, an official rang a bell, alerting the birds that it was supper time. Without fail, the pigeons would swarm San Marco in search of the official’s grain. Aside from providing them food, Venetian officials also imposed strict laws guaranteeing the birds’ safety. If anyone harmed a pigeon, he or she would be arrested. For first-time offenders, they’d be fined; for repeat offenders, a trip to prison awaited them. Venetian citizens, for their part, viewed San Marco’s pigeons as sacred—it was not uncommon for individuals to leave legacies for their care or request saintships for them in the local calendar.

In 1848-49, the Piazza’s pigeons, not unlike their ancestors, found themselves recruited for wartime service. A possession of the Austrian Empire since 1797, Venice revolted in 1848, forming its own state, the Republic of San Marco. The Austrians eventually initiated a blockade of the Venetian Lagoon and bombarded the city. Throughout the blockade, the feeding of the Piazza’s pigeons continued unabated, even though the city’s population was starving. Some of them even carried messages out of the city in an end-run around the blockade. It was only in the last days of the conflict that a few individuals resorted to the unthinkable and ate some of San Marco’s pigeons. In August 1849, the Republic surrendered to the Austrians, becoming a Hapsburg province for 17 more years.

By the modern era, the city’s pigeons had lost their luster. Tourists still loved them, and a thriving industry had popped up, supplying visitors with corn to feed the birds. City officials, however, were frustrated that the city’s pigeon population had ballooned to 60,000, even though the city could only accommodate about 2,400 of them. Pigeons were blamed for damaging art and architecture—their highly acidic poop allegedly caused structural damage as it seeped into fissures, while their constant scratching and pecking damaged marble monuments. They also, per officials, spread disease and attacked the customers of hoteliers, restaurateurs, and other merchants. Pigeon advocates chalked most of these issues up to pollution and reckless tourists.

Much to the chagrin of tourists, in 1997, Venice banned the feeding of pigeons everywhere except for at Piazza San Marco. Naturally, this caused the city’s pigeons to congregate en masse at the Piazza. In 2008, the city finally banned the feeding of pigeons at San Marco. Violators would face a €500 fine. While the ordinance merely annoyed tourists seeking pictures with the pigeons, it carried with it serious economic consequences for the Piazza’s 19 licensed bird seed vendors. Before the ban, vendors had offered tourists 3.5 ounces of corn for $1.30. On a good day, a vendor could clear more than $100. Outraged by the ban, the vendors argued that most of the damage to the Piazza was caused by smog. Vendor Gianni Favin noted the pigeons’ legacy at San Marco: “There have been pigeons in St. Mark’s Square for a thousand years,” he angrily remarked to the press. “To see the piazza without pigeons is like seeing a tree without its leaves.”

Vendors and tourists weren’t the only figures angered at the ban—animal rights groups vigorously protested as well. Shortly after the ban’s enactment, a “band of animal lovers armed with skull-and-crossbones flags” cruised up to the Piazza in their speedboat and hurriedly scattered 20 pounds of birdseed for the pigeons. They struck twice at dawn and once at midday, daring the police to fine them. But the stunts did not dissuade city officials from lifting the ban.

In the 14 years since the ban was implemented, mass colonies of pigeons continue to reside at Piazza San Marco. Some tourists still feed them on the sly, even though the fine has now been raised to €700. Having been a fixture since the 1200s, it seems that the legacy of San Marco’s pigeons will be a hard one to eradicate.

Sources:

- Ali, Shafqat. St Mark’s Square Pigeons Refuse to Budge. The Nation, 9 July 2018, https://www.nation.com.pk/10-Jul-2018/st-mark-s-square-pigeons-refuse-to-budge.